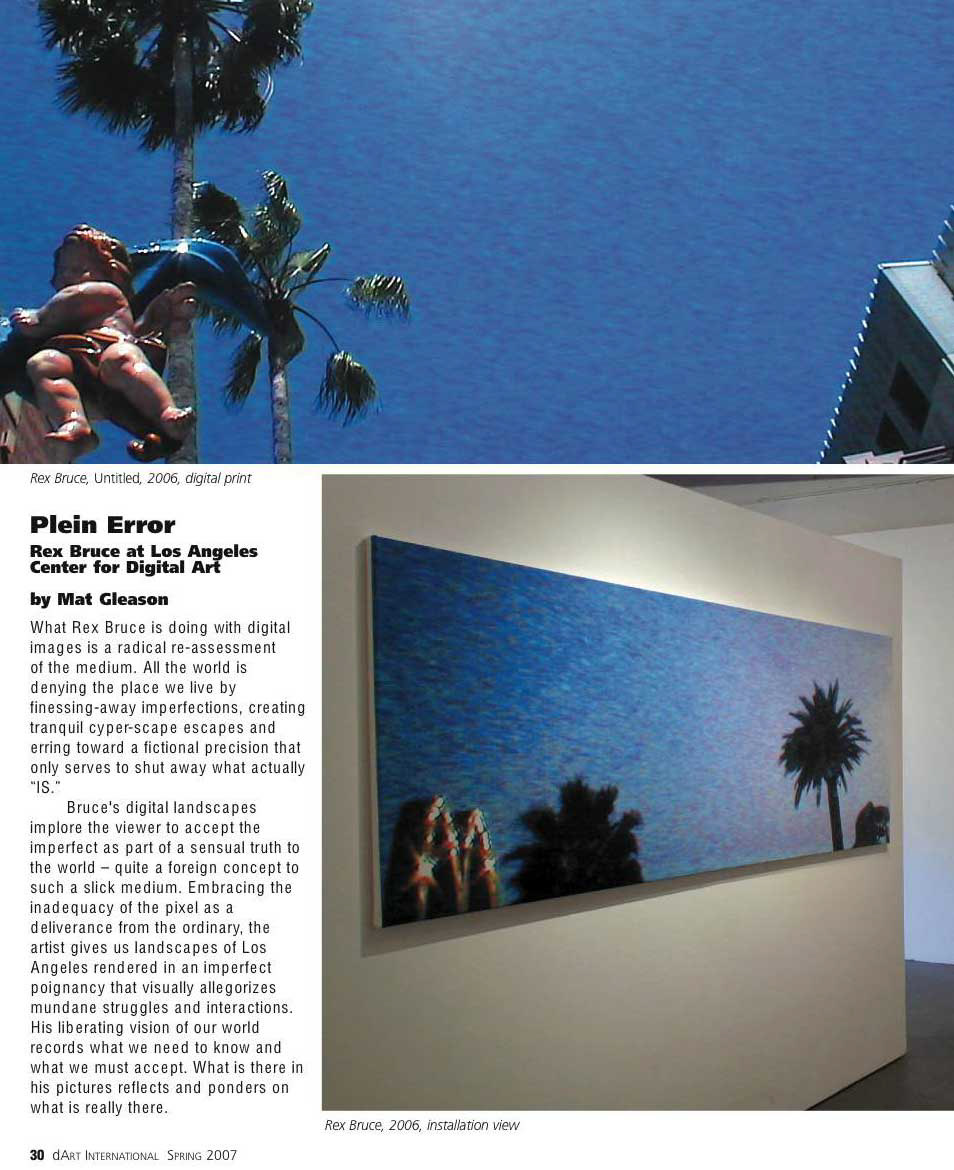

Rex Bruce has been working with art and technology for many decades, distinguishing himself as an innovative artist, educator and curator working in a wide variety of computer related disciplines over the course of his career. His focus is experimentation with a variety of low resolution digital cameras, using them as a starting point for inverting the conventions of photographic art and digital imaging.

His landscape images are iconic of Los Angeles where he works and resides. Within sun drenched sky-scapes the very tops of golden arches, street lamps, vernacular decoration and architecture jut upwards into the frame. Images are shot towards the sun and composed cropped with subject matter at the periphery. Lens flares, colorizations, and artifacts of the cameras are systematically cultivated and refined. Objects appear in shadow, without detail and difficult to discern. Some images are taken with a cell phone camera where the subject then becomes the "air" in which mobile communications are transmitted. Often included are telephone poles and slack wires strung between them, an ironic choice considering the instrument with which they were photographed.

In a move away from using the artifice of image editing software, only simple adjustments are used exclusively to bring out the usually avoided artifacts of digital imaging. Tone, hue and saturation adjustments emphasize banding and pixilation, as well coloration in shadow areas. The recombination of imagery usually achieved by compositing layers are made by skillfully discovering tableaux "narratives" occurring in the heavenward views of Los Angeles.

The end result bears a relationship to the work of painters. Over the centuries many artists sought to advance their capabilities to create an ever more realistic representation of what could be seen. Eventually an experiment began with the nature of the paint itself and other purely aesthetic concerns regarding shape, texture, color and form (to name a few). Similarly, this work breaks off from the pursuit of the "best image possible" into an exploration of the formalistic attributes (and conceptual implications) present in the emergent technology of digital imaging itself.

The unwanted becoming wanted is a thematic undercurrent in his work that bears a relationship to more broadly philosophic ideas. It is an aesthetic move that brings the "margin" into the "center."

REX BRUCE: NO LIE IN THE SKY

By Peter Frank

, Critic for L.A. Weekly, Principal Curator Riverside Art Museum

Rex Bruce operates first and foremost as a digital artist, and in the images that have most lately resulted from his long experience with the computer he sets out to expose the nature, however overlapping, of both photography and digital art. In the process he embraces a vision of his town that is at once a cliché and a revelation.

Empty blue sky predominates throughout Bruce's series of large photographs - images that one assumes are composited, but turn out not to be. (As he writes, "I am more interested in the artifacts each camera I have generates under certain lighting conditions. I only adjust and use print settings to bring these elements to the foreground. As opposed to 'correcting' images, I 'incorrect' images.") The expanse of sun-infused azure is framed (or, less frequently, bracketed) by a tree, building, and/or billboard - a corporate logo, perhaps, liberated from its skyscraper, or an explosion of fronds bursting like fireworks far above our heads. In some senses it's an ironic view of L.A.; that most horizontal of cities, Bruce shows, fairly bristles with things above our heads, but we have more reason to avoid looking up (so as not to scald our eyeballs) than to look up (as we would in a vertical city like New York), and whatever is above us isn't worth the gander.

No poetry but in things, William Carlos Williams cautioned; and in these banalities Bruce finds a goofy, loping rhythm and a cinematic poignancy. Their emptiness is more profound than that of the sky they frame; we know that galaxies lurk behind the blue expanse, whereas all that live in the structures above our sightlines are tree rats, pigeons, and desk jockeys - oh, yeah, and the occasional putto or Art Deco detail, charming as much for its incongruence as for its artfulness. The Los Angeles above us does not lack for soul; it lacks only for substance - what was once, but can no longer be, said of the Los Angeles around us.

Of course, Bruce's upward aim belies a famous given of L.A. life the city has struggled to outgrow. By finding blue sky in the Los Angeles basin, Bruce either subscribes to or ironically mocks the Chamber of Commerce pretension that the region has licked its smog problem. But Los Angeles' skies are the real fakers here. Except in Inland Empire-level emergencies, the polluted air one breathes never looks like polluted air. It looks like air. Off in the distance, haze whitens the blue - or, worse, grays or browns or even khakis it. But straight up it's blue, end of spectrum, end of story. Clouds are the exception, not the rule, and they do not figure in Bruce's reportorial fictions except to enhance their seeming veracity - local color, as it were.

Bruce's images are reportorial in that he presents them as recorded detail. They are fictions in that, in good noir fashion, he casts that detail against a deceptively vacant sky, positing a narrative, or at least mise en scene, that argues with the human frailty below. For all their accuracy, the images are not "true to life," at least the life we know. They reveal an alternate truth - a truth so alternate that we sophisticates are certain it's been invented, that Bruce has montaged them in Photoshop. But he hasn't; in defiance of his own long experience with digital media, he has eschewed the patchwork fabulization that now infects the whole of our visual culture and presents us with just the facts. And he teases us into believing him, or, conversely, into refusing to believe him.

These big pictures, in fact, are no longer photographs, at least as we understand the photographic medium to be documentary in its employment in the quest for visual accuracy. As Mat Gleason has observed, they are more like paintings, Bruce having expanded the images' size to reveal their components Should we get anywhere near them, we see, unavoidably, the pixels that comprise these near-muralic images. We can read these pixels like brushstrokes in a Constable. Bruce's craft, of course, is light years from Constable's, and he makes no pretense about keystrokes equaling brushstrokes. Rather, Bruce wants to elucidate the technical facture that undergirds his apparencies - and to unfold thereby not just the city he inhabits but the medium in which he has specialized since its infancy.

Long a moving force in L.A.'s digital fine-arts community, Rex Bruce has watched as the tools he and his colleagues once labored to master have been made available to whole industries and most of the rest of humanity. The genie is out of the bottle, and Bruce feels a responsibility - patronizing, perhaps, but earnest and conceptually subtle - to remind the rest of us that photography is a medium that feigns rather than assures truth, and that digital art compounds this illusion. Everyone is supposed to know that, and perhaps in a generation or so everyone will. Even without resorting to montage, Bruce's series of skyscapes exposes substrata of vision, and thus demystifies both the camera and the computer. He shows how the photographer's - even the journalist photographer's - own subjectivity reflects in the digital hall of mirrors. It's not news, and no occasion for a call to arms. Indeed, on the discursive level Bruce presents his revelations as words to the wise. He is more bemused, even amused, by the potential for endless elaboration the marriage of technologies provides than he is outraged. Picasso called art the "lie that tells the truth," that is, the visual fabrication that awakens us to realizations about our universe. And in an era of "truthiness," Bruce avers, telling the actual truth rings false, and the outright lie of art rings true.

Peter Frank

April 2007